Andrew Mann

An ultra-low density super Earth

HIP 67522b is a 17 million-year-old jovian-radius planet, first reported in Rizzuto et al. (2020). This was the only known 'hot Jupiter', which made it pretty important for studying things like planetary migration.

We were approved to observe the planet's transmission spectrum in Cycle 1 of JWST. The goal was to study the planet's atmosphere from its transit depth as a function of wavelength. A quick primer on how transmission spectroscopy works can be found here.

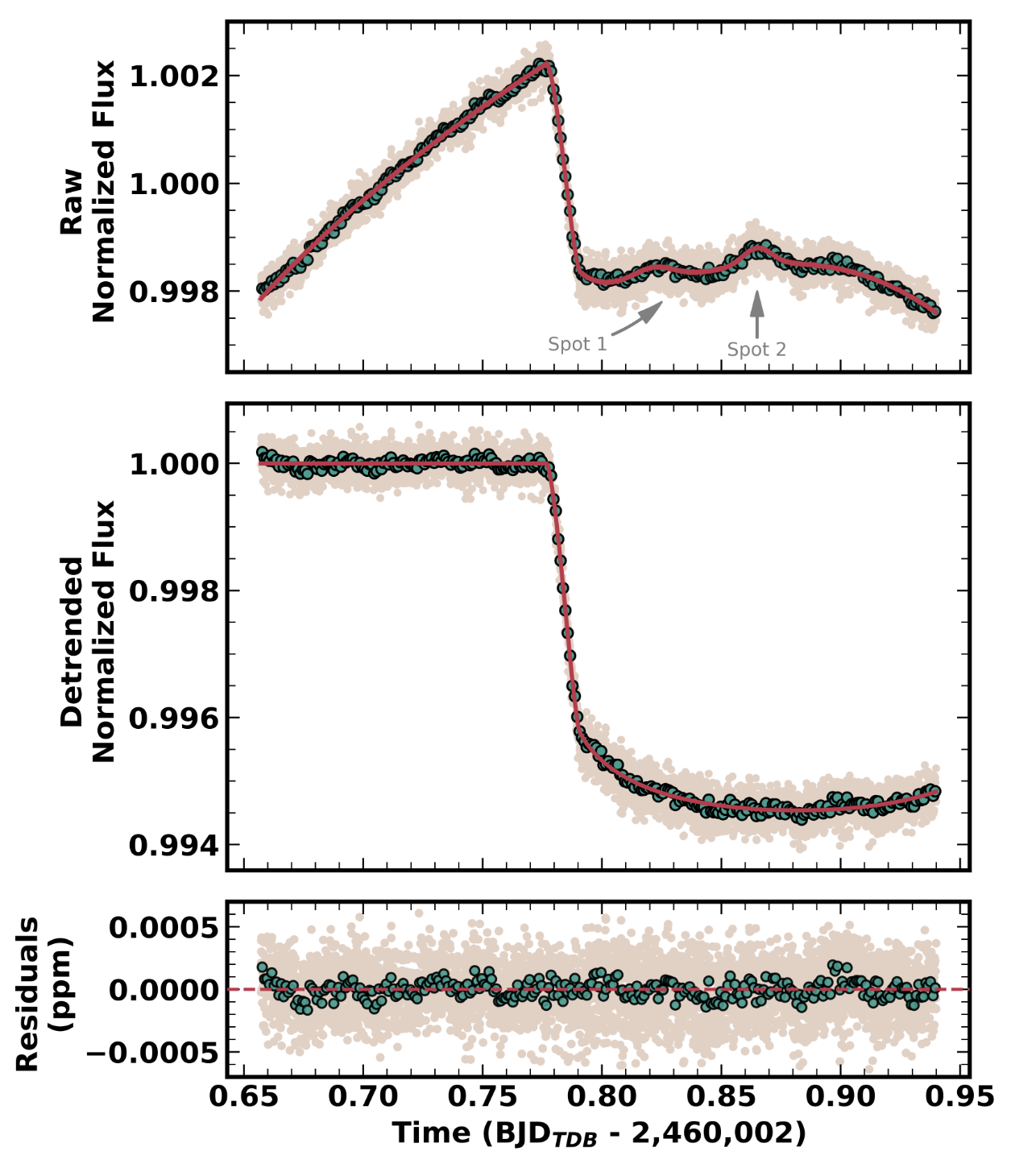

The good news is that the JWST data is exceptional all on its own. After all, look at how absurdly precise those residuals are. That's misleadingly bad actually, as it's the combined curve and hence includes variations in depth due to the planetary atmosphere.

As it turns out, we didn't even need most of this complementary data to get a really great result anyway.

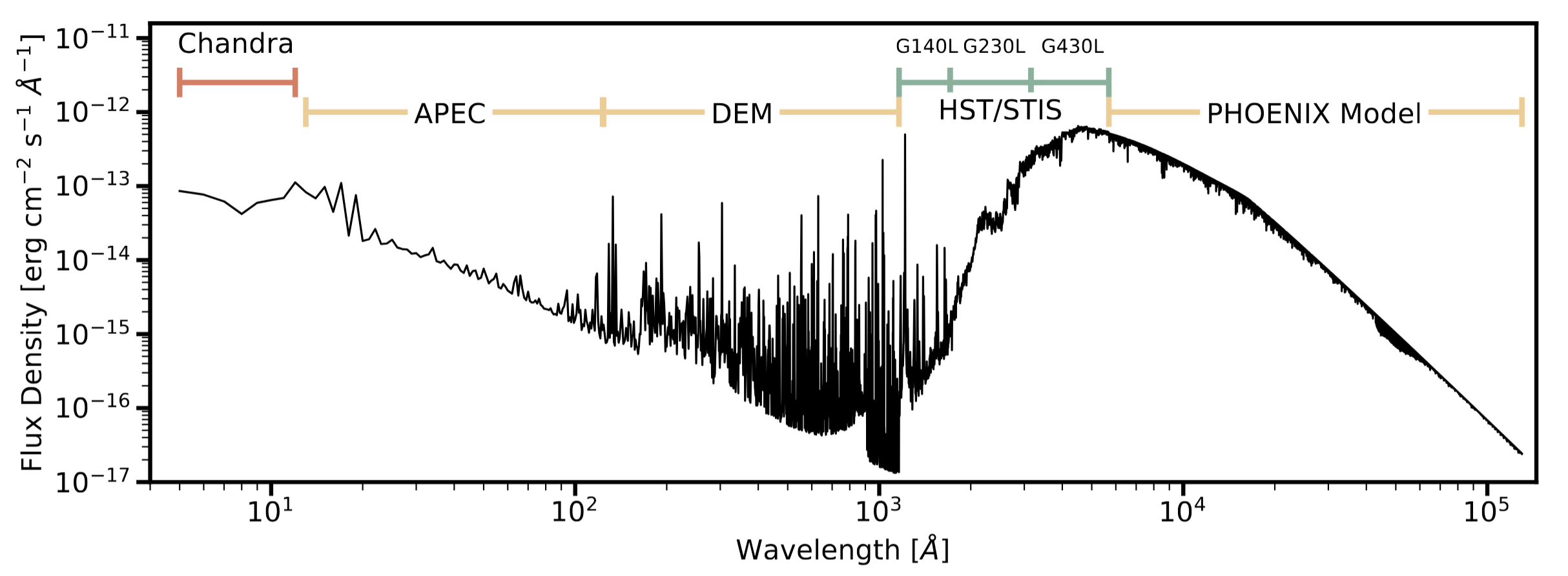

With the JWST data in hand, the first thing we did was get a full spectrum (UV to infrared) of the star. This is needed to model photochemistry - how stellar radiation impacts the planetary chemistry. Take a look at this amazing spectrum:

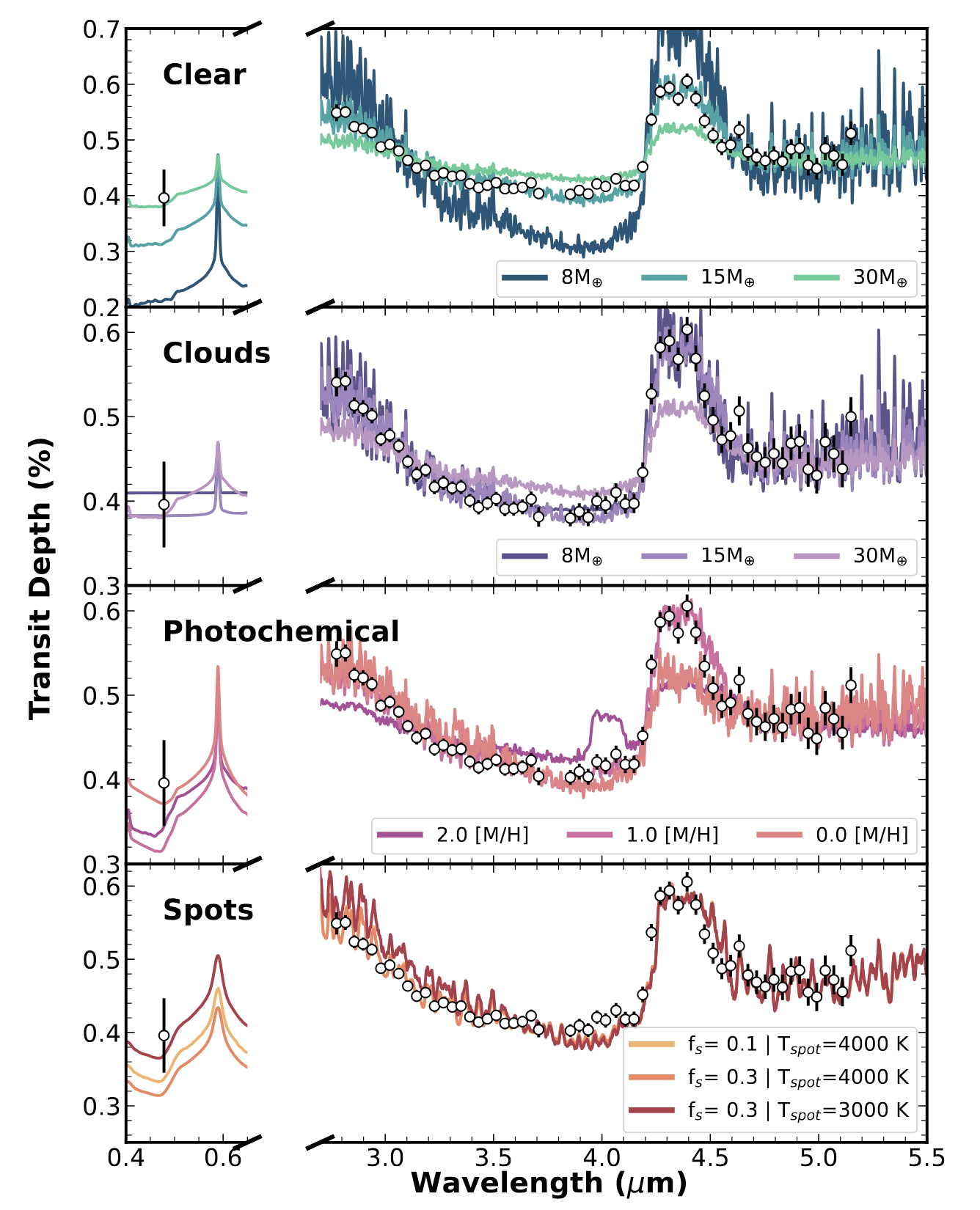

Next we turn the JWST data into a full transmission spectrum - transit depth as a function of wavelength. Then compare that to a grid of models. The below plot shows the transmission spectrum compared to three different models for four scenarios.

The model construction is pretty complicated, so for here we will just focus on the effect of 1) planetary mass, 2) stellar surface spots, and 3) planetary clouds.

Let's start with mass. A prior study had found you can measure the mass of a planet from its transmission spectrum. This works through the scale height - a lower surface gravity planet will have stronger features because the atmospheric material extends to higher altitudes (so a wider range of absorption levels). A more recent study had suggested this was more complicated than it seems because of complex degeneracies between mass and other parameters. However, they were focusing on small planets (1-2 Earth radii) that tend to be dense and hard to characterize. Young planets are expected to be puffy, where this method should work better. Indeed, the transit depth of HIP 67522 varies by ~50% over the JWST data, 10x more than is seen in a typical transmission spectrum. The conclusion is that HIP 67522 must be very low mass (about 15 Earth masses). This is shockingly low - a similar radius old planet would have a mass of 200-300 Earth masses, 10-20x more than HIP 67522. This makes HIP 67522 one of the lowest density planets known:

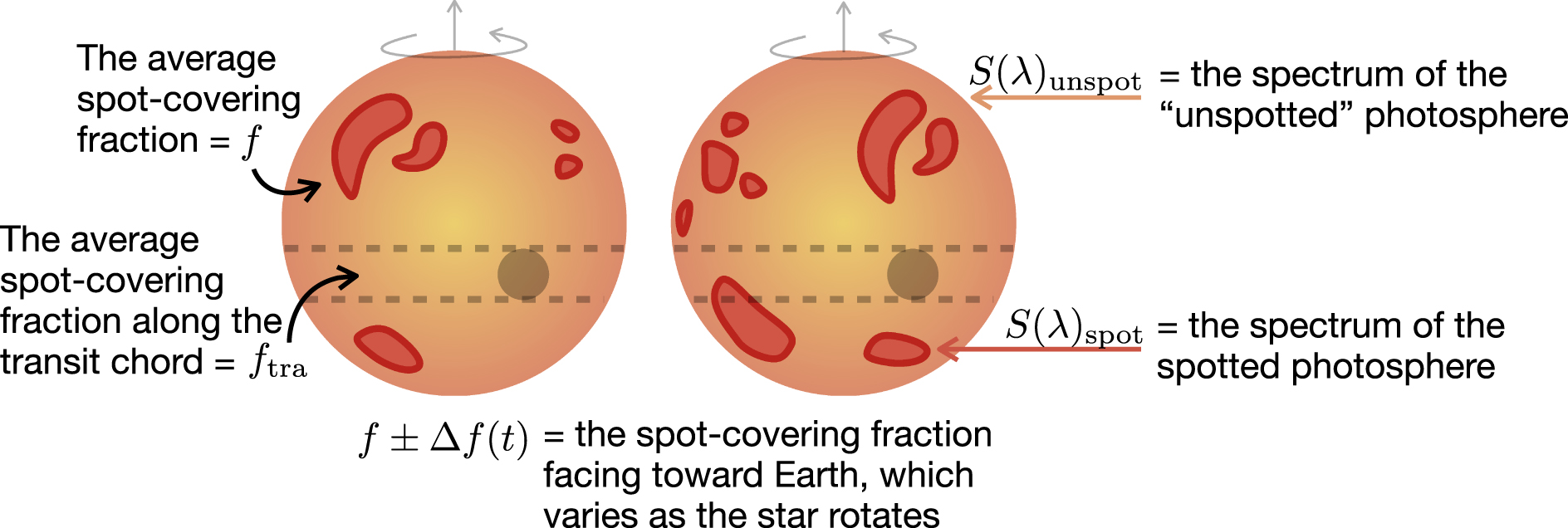

Let's move to stellar spots. Spots are known to create problems This figure summarizes the effect:

If a star has spots, the planet is crossing a region of the star that is hotter/brighter than the other regions of the star (because those other regions have cold spots). This reverses if the spots are hot or the planet is crossing the spotted regions. The effect is problematic because you don't have independent data that can tell you if there are spots in regions the planets isn't crossing, and you have few to no constraints on the properties of those spots.

The good news for HIP 67522b is that it seemed not to matter at all. The carbon-dioxide feature we see in the JWST data (at 4.4 microns) is not present in spots - so no spot coverage can reproduce it. This is clear in the "Spots" panel above - varying the spot coverage changes the blue end (a water band) but has no impact on the major feature on the red end. It has effectively no impact on our result.

Last up is clouds. Clouds can change our derived mass, depending on the kind of cloud. The good news is that clouds cannot make features stronger - so they can only make the planet less massive, not more. So the planet is low density regardless. There's also a kind of minimum density where the planet is unstable on short timescales (the atmosphere is unbound). That hits around 8 Earth masses. So we are comfortable saying this planet is between 8 Earth masses and 20 Earth masses.

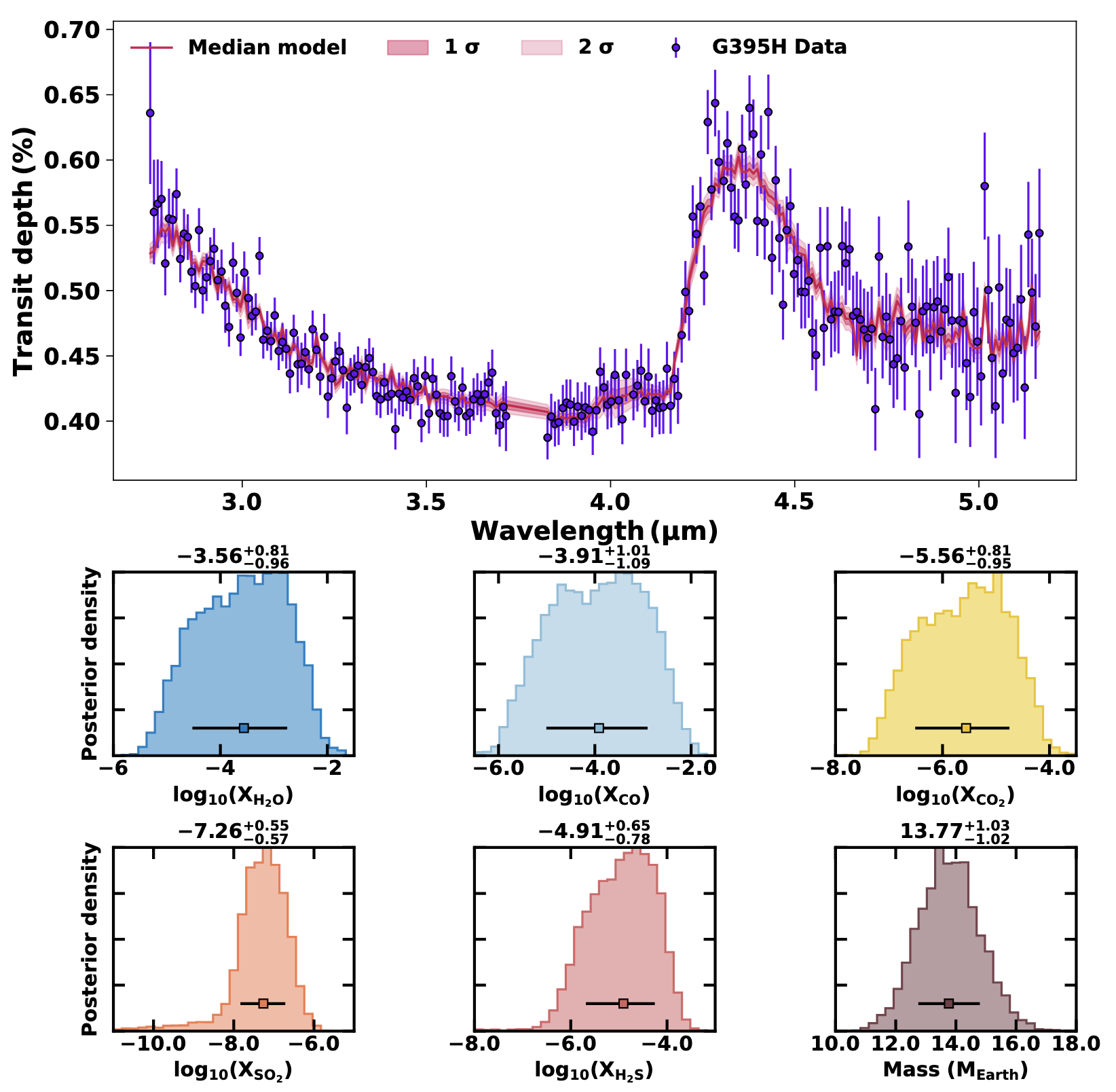

Another approach is to run a retrieval. Here is a decent summary of how retrievals work. I have personal concerns about how some retrieval codes work which I cannot fully flesh out here. One big one is how they handle spot modeling, which is especially important for these young stars. However, retrievals can be very powerful for exploring the parameter space. Our retrieval fit is here:

The big result is that the mass is even more constrained to 14+/-1 Earth masses, a shockingly precise result. The higher precision over our grid fit using PICASO models is, in part, because the retrieval found no model including a cloud could reproduce the data. Indeed, looking over our earlier model fits roughly agrees with this - the resulting cloud properties are almost unphysical. In the end, both results agree but with different final uncertainties. Whichever you prefer, the planet is definitely not a hot Jupiter!